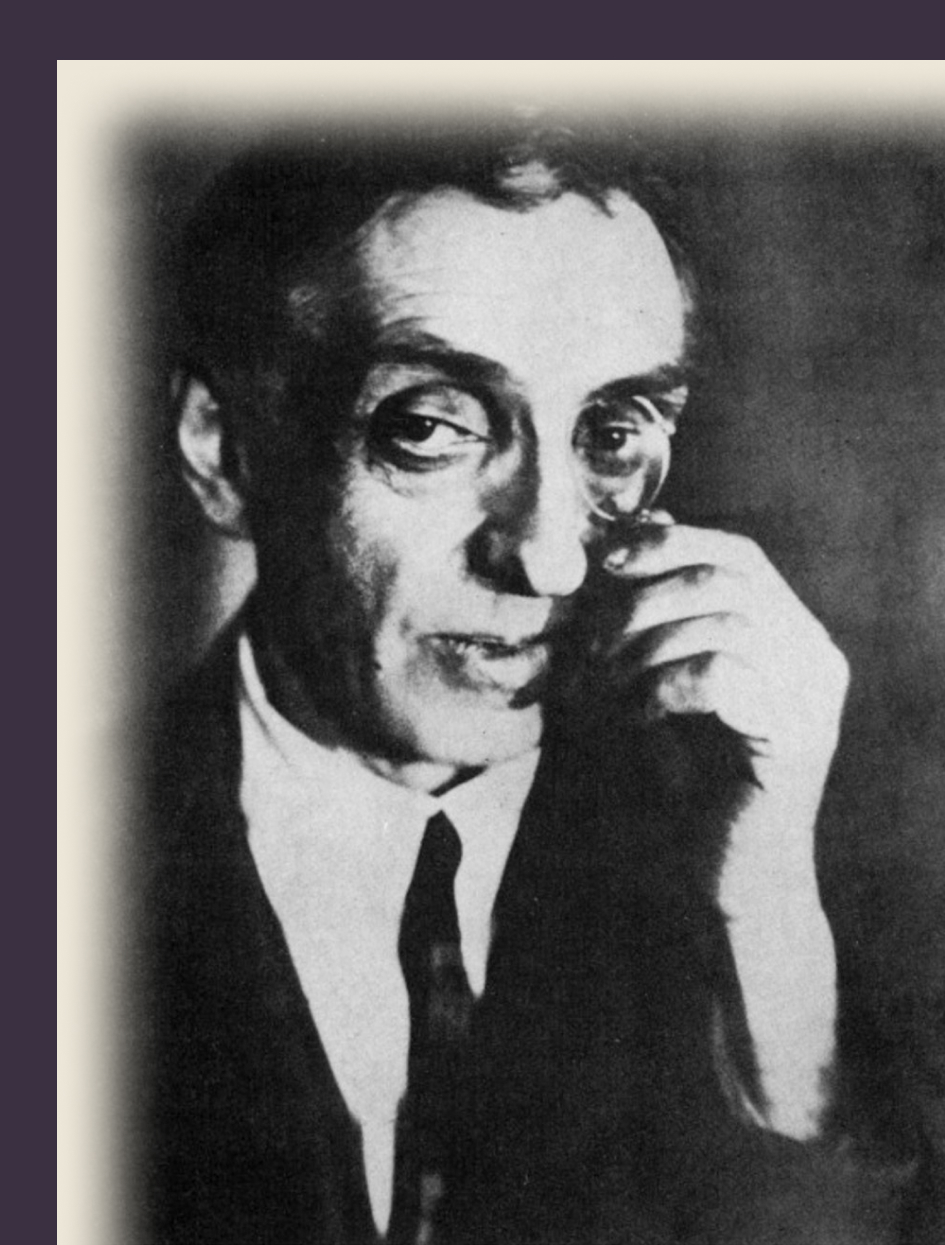

One of the most striking, touching, and deeply moving poems by Mikhail Kuzmin. Surprisingly, this poetic masterpiece is entirely diaristic in nature: the autumn and early winter of 1920 were bleak for the poet, marked by financial difficulties and ill health (“My hands trouble me terribly. I fear my fingers might fall off…”). Nevertheless, his creative work (poetry, translations) continued, and creative associations — the painting by Vasily Surikov — were the first things that came to mind when describing his own impoverished life. Let's recall this painting.

The main impression it gives is the dignity and strength of spirit of those in confinement and forced to endure deprivation — Alexander Menshikov and his three children, his wife had already passed away by that time. Their only consolation is that they are together and that the holy book is nearby. This mood carries over into Kuzmin's text, where the theme of togetherness becomes a saving grace: the shared experience of hardships, the shared anticipation (“All sorts of rumors. This distinguishes Petersburg from Moscow. There they live crushed, hoping for nothing”) and the loss of hope, the shared prayer… (“Not a thought, but a premonition of a thought, that suddenly this is forevermore, until the end of life, terrified me, but God, of course, will not allow it.”)

Interestingly, the poem reached abroad by being memorized and was dictated to Zinaida Gippius, who published it without the author's name (instead, it was attributed to “living people in Russia”). This was not so much due to the literary circumstances of this publication (the attitude towards Kuzmin) as to political motives: an anti-Bolshevik poem published on behalf of the anonymous “living” left in Russia (“This is their winter, and these verses are their story.”).

The brightest stanza is the fourth, and it is also the most stoic in tone, even though it is just a plea and it is unknown if the wish will come true. This stanza is very carefully crafted: plain and simple. And it is perfectly clear that this plea/prayer is a benchmark of spiritual state set for oneself (and the beloved) that must be achieved; otherwise, one might as well say goodbye to life.

It is worth noting that for Kuzmin, faith is always something intimate, homey; its rituals are performed in the interiors of a room and almost never in a church. For him Christianity is above all love. And the angels, constant characters in his poetry, accompanying him in joy and sorrow, behave quite homey as well, they can even cry from helplessness. But for Kuzmin, this is completely unimaginable; there arises a gesture of resistance (“No, we're just in exile, just in exile…”) and the overcoming of life's hardships through love, when the transient home (in other words, life) is warmed by love on the very brink of destruction. And what an interesting rhyme: see — tenderly!

The motif of exile is perceived completely differently in the first and penultimate stanzas. In the first, it is punishment and almost demise; in the penultimate, it is a temporary state from which one can return to life with its human warmth and constancy.

Remarkable is the twice-repeated color: pink for Kuzmin is always calm, life-giving (“Soft pink air, as if there were no war or revolution…”, March 1918; “What wonderful weather. In the twilight such blueness and rosiness, as if it were spring, Italy, and everything was calm. During the day, the wind chased away the clouds, and there were delightful pink-green flecks of mother-of-pearl.”).

A miracle happens literally before our eyes. The downward gaze first sees disintegrating shoes, then rises following a ray of light to the gilt Archangel, and, meeting the angel with the inner gaze, in the premonition of a possible fall (in other words, loss of hope), stops on the familiar face and revives it with love.

I. K.

December freezes in the rosy sky,

The unheated house grows dark and grim.

And we, like Menshikov in Beryozov, lie

Reading the Bible, waiting on a whim.

Awaiting what? Do we truly know?

What salvific hand might appear?

As fingers swell and split in woe,

And shoes disintegrate, year by year.

Of Wrangel, not a whisper’s heard,

Days drag on, leaden and gray.

On the gilt Archangel, undisturbed,

Lights merely shimmer and sway.

Please grant us patience strong and true,

A gentle spirit, and sleep light,

And holy reading of the books we knew,

And an unchanging sky so bright!

But if the angel bends in sorrow,

Weeping, "This is forevermore!"

Let the star that led me, on the morrow,

Fall like a sinner, to the floor.

No, we’re just in exile, just in exile,

Oh, my poor love, don’t you see?

In gentle streams, not fierce and riled,

My very blood warms tenderly,

Tinting the cheeks with rosy sheen,

Our transient home no longer cold,

And we, like Menshikov once seen,

Read the Bible as days unfold.

1920